soundgarden

In this entry, I will focus on the theory behind Soundgarden and outline my approach in adapting Schafer’s acoustic design principles, explaining some of the reasoning behind the sounds and systems that I’ve been silently adding over the previous weeks.

Principles of acoustic design 🔊

Schafer mentions four principles of acoustic design (The Soundscape, p. 238). I have summarized them into single terms and will explain them in the context of my own work with Soundgarden.

Composition: Sounds in a game environment should be chosen and arranged such that they contribute to an immersive and harmonious soundscape, while respecting the player’s auditory threshold, i.e., avoiding harmfully loud or imperceptibly quiet sounds.

Meaning: Sounds should be more than mere functional cues. A sound may already hold symbolic depth or may be imbued with it when integrated into a game environment. This may allow for additional emotional layers, and enhancement of existing narratives. Sounds may resonate with players when using auditory symbols, evoking memories, emotions, and personal connections.

Timing: Sounds may occur at different points in time, constantly overlapping or alternating with each other. A sound may have its own rhythm and tempo, and/or may be controlled by the rhythms of other actors and systems in a game.

Self-regulation: Sounds should be capable of moderating themselves to prevent auditory overload. This is especially important when a sound is driven procedurally, where a range of outcomes, including extreme ones, is possible.

What I find interesting about these principles is that sound may be substituted by or combined with other embedded media. These principles appear to fit a systemic view of a game: Schafer speaks of acoustic ecologies, whereas Soundgarden constitutes the ecology of a game environment. I’m not using the term ludic ecology here, since it suggests too much emphasis on the process of play, whereas I see a game environment as playful, in terms of an interplay between all these different elements that comprise it.

Just like bird calls may occur in certain patterns during specific times, marking a location, regulating themselves not to dominate the soundscape, other game events and outputs of various systems may do so as well. Looking at game making through the lens of acoustic design therefore allows me as a game designer to have a systemic - i.e., ecologic - approach to creating a world and its interactions.

From reality to simulated reality by applying observed patterns 🔎

Real ecologies and their phenomena can provide us with pointers for systemic design.

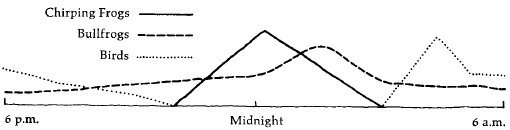

The figure below (Schafer, The Soundscape, p. 231) depicts the audible activity of three different animal groups over a 12-hour period. The curves which are derived from observed animal activity resemble curves that game engines use to set continuous values.

We could now naïvely copypaste these curves into the game engine and have them control the activity of actors directly. However, to adapt a real-world phenomenon, one must understand the relationships that led to its emergence. Specifically looking at the bird activity, there is activity starting at approximately 3 AM and ending at around 10 PM, which appears to correlate with sunrise and sunset. This leads to the conclusion that it is not the time of day that affects activity here (and one does not need to be an ornithologist to know that birds don’t wear watches) but rather brightness, affected by the increasing and decreasing intensity of sunlight throughout the day. Instead directly controlling bird activity by a ‘birds’ curve, the birds are programmed to observe the intensity of the sun. In informatics, an observer pattern is a common solution for having multiple entities observe a certain behavior and run some code when the observed entity dispatches an event. In a way, the optimal technical solution here mimics a real-world behavior. The introduction of sun intensity as a systemic factor may in turn inspire more thinking about other entities in the game world that could be affected by its variations.

On Normalization 🎚️

Whenever a logical component - for example a module in my music system, or the day night cycle indicating sun intensity - uses float parameters for input or output, I map them to a range between 0 and 1, also referred to as a unit interval in mathematics. Not only allows this for easier connection of different components because values don’t need to be remapped, it allows for “logical compression”, i.e., deriving meaning from a value and its name. 0 will always be the least of something, or off, whereas 1 will always be the maximum, the most intense, just like the parrot calls I described in the previous post. If all parts of the music system, as well as game logic, use normalized values as in/outputs, connecting the individual components becomes trivial. This may facilitate some experimentation - one might try connecting systems for interesting results. What if the sun intensity does not just affect activity of animals? For example, player movement speed could be in proportion to sun intensity, affecting how the player moves and possibly how they perceive their environment, with slower movement perhaps leading to more attention towards the immediate environment… Some connections may lead to profound impacts on gameplay.

Rethinking the music 🎼

Constantly playing background music seems to closely resemble the act of moving through the world with headphones in your ears, possibly shutting off the world around you. Soundgarden is about listening to the interplay of sound and silence, and gathering meaning from it. As of now, music is playing constantly. While I don’t think that having constant background music is necessarily against the principles of acoustic design, I do think that its current implementation does not leave enough space to listen to the environment. To address this, and because I think it will lead to more musical variation overall, I have decided to move over the ‘extradiegetic’ sounds into the world. I’m also thinking of introducing sounds that seem to come from inside the game world but that can’t be properly localized, inspired by my own experiences with low-frequency hums (off-topic, but here is an excellent video on these mysterious low-frequency hums that occur in our world). Anyway, bringing more music into the world will mean that I’m going to have to come up with new objects that emanate sound. For those, I will likely move into a slightly more surreal direction. Looking back at some inspirations I described in my first post.